Venice: full of architectural absurdities

Architects have built a whole world of jargon in Venice. It is impossible to visit the 2025 architecture biennale, the world’s largest and most influential architecture exhibition, without encountering tortured language and hundreds of made-up words. Here are a few I collected during a half-hour wander around the displays during press week last week:

‘intelligences’

‘contestations’

‘spatialities’

‘reimaginings’

‘mono-physicalities’

‘intra-realities’

‘un-disciplining’

‘sub-dimensionings’

and — this was my favourite — ‘the circulations of things’ (I think it means ‘manufacturing’).

Not every display is incomprehensible. But why do so many of the biennale’s 750 participants make up grandiose non-words? Because they are not addressing the visiting public; they are talking to one another. The purpose of jargon in any discipline is partly to impress insiders and partly to exclude, to signal to outsiders — us — that we are not being spoken to, no matter how interested in the subject we may be nor how relevant it is to our lives. Exclusion is an effective way of shutting down counter-argument, avoiding scrutiny and dodging questions. Jargon is arrogance mixed with cowardice.

During press week every pavilion has a launch event, usually with the exhibiting architects and artists reading out their manifestos. Some are great, others empty out like clown cars.

Unintelligible labelling against hundreds of exhibits in 66 national pavilions, a 317-long exhibition hall and 11 off-site events is an exhausting experience. If anything, biennale jargon is worse than it was two years ago, which suggests it serves its purpose very well. ‘Contestating’ about it is ‘sub-intelligent’.

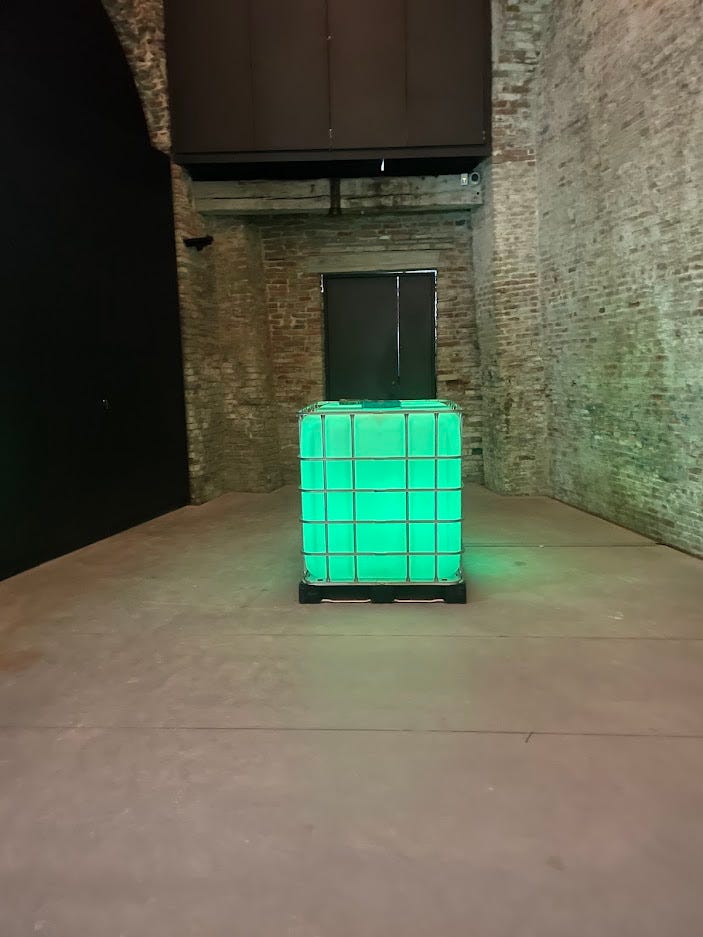

There are good things to see in Venice, and not everything is badly labeled. The installation in the Chilean pavilion, for example, reports on the black-box architecture of the enormous artificial intelligence servers being built by American big-tech companies on its fragile land.

Mute creepiness in Chile’s pavilion

Uzbekistan focuses on the future of one of the last big building projects of the Soviet Union, the Sun Institute of Material Science. Built in 1987 near Tashkent, it held massive solar furnaces that aided the study of how materials behaved in extreme temperatures. Forty years on, how might a long-deserted, late-modernist concrete mega-campus be resurrected and become something else?

Sunny optimism in Uzbekistan’s pavilion

I like Poland’s offering, the unambiguously titled ‘On Building a Sense of Security in Architecture’, dedicated to all the ways human beings try to protect their homes, from hi-tech security devices to absurd rituals, like piles of salt in corners.

Helpful signs in Poland’s pavilion

Estonia, in an offsite palazetto facing the Grand Canal, explains why so many building projects are doomed to fail, with neon perspex architectural models and a scripted tragi-comic drama.

Neon perspex blocks in Estonia’s pavilion

Elsewhere, the ghost of Steve Jobs haunts Venice. There was Norman Foster, speaking at an event in an exquisite, 15th-century palazzo overlooking the Grand Canal, when he suddenly — unnervingly — swerved into talking about iPhones. The device was a universal success, he said, because it was “designed by a designer for designers … And it was not what the market needed; Steve created the market.”

Listening to Norman Foster talk about iPhones in the Palazzo Pisani Moretta

Well, yes. Henry Ford thought he was destroying mass transit, only to invent the traffic jam. Among the iPhone’s many consequences, you could argue that by nullifying a bunch of useful-but-cumbersome things like compasses, newspapers and paper maps, Jobs invented another modern scourge: the pedestrian staring at their phone.

Phone-zombies — or ‘phombies’ — are a daily menace all over the world. They are the people who absolve themselves of the labour (and it is labour) of the unspoken, multiple negotiations with others required to navigate a street safely, and instead offload their share of the work onto the rest of us by behaving like human snow ploughs.

They may be winning in other cities, but Venice frustrates them. The streets, alleys, paths and bridges are so dense that it’s impossible for non-Venetians to navigate without a map. But mobile location technology doesn’t work well here. The navigational blue dot is confounded, forever changing its mind, re-routing itself, doubling back. That leaves phombies, Jobs’s accidental legacy, careering into one another, stumbling down blind alleyways and smacking into dead ends. In a city with more than 30 million visitors a year, it’s satisfying to watch, with the added thrill that they might blunder into a canal. A kind of restorative pedestrian justice.

I tried not to turn into a phombie, but in Venice it’s hard. Before you know it, you’re a pavement hazard, meandering blindly after that blue dot. On my way to an event, my phone-map told me I was a block away from Marco Polo’s house, so I thought I’d take a look. But the dot became spectral: it kept disappearing then reappearing in different alleyways. Marco Polo found his way to China from 13th-century Venice; with Jobs’s universal success, I couldn’t navigate my way around a corner.

Foster was promoting a glittering, 37-metre tubular ramp created by his foundation and by Porsche, a ‘functional bridge and gateway that explores the future of mobility, connecting with new electric modes of transport for water and land’, which, in a desolate field, was one of the most coherent descriptors I read all week.

‘Gateway to Venice’s Waterway’ at the Arsenale lagoon

One review described the ramp as looking like an experiment in parametric design from the early 2000s. All I could see was Venice’s favourite seafood delicacy, often served fresh from the lagoon, the supernaturally sweet and delectable canocchie — or mantis shrimp.

Back to London. The thing about the National Gallery is that everything about its big, grand portico overlooking Trafalgar Square screams ‘ENTRANCE!’. It looks like all the other entrances to national galleries the world over. If you had never visited the British collection before, every instinct would tell you to head straight up the big, grand steps. The task for whoever got to remodel its Sainsbury Wing, the entrance to the gallery since 1991, was to convince people to twist their heads and turn left.

The National Gallery’s new-old Sainsbury Wing

Annabelle Selldorf’s remodelled Sainsbury Wing, which reopened last week, is meant to achieve that. There’s a lot more space, height and clear glass than before, the gates have been brightened and the sign is illuminated. But the queues and the dreary airport-style security system are still there.

Other things:

Bookings are open for the V&A East Storehouse ‘Order an Object’ service. The Storehouse, in the former Olympic Village press building in Hackney Wick, opens on May 31 with an entirely new museum model, something between a warehouse and an archive. Anyone can order anything from the stores to look at and study, for free, seven days a week. I’m going to be reviewing the new museum and the ordering service for the Telegraph. I’ve already whiled away an afternoon scrolling through the online catalogue. You can start ordering here.

The Manifesto House, Owen Hopkins’ new book about the houses that architects built as statements of intent — often for themselves — may look like a coffee-table book but it is far more interesting and radical than that. (My review for the Financial Times is here.) Hopkins is director of the excellent Farrell Centre in Newcastle and co-curated the British pavilion at the Venice biennale.

Other things I’m working on:

A long-form piece about secret culinary lives

A story about restoring modern art

More book reviews

Find me on Bluesky and Instagram

My website, where you can find a selection of my work, is here.

So with you on the labour of avoiding phombies. In absolving themselves of all responsibility it makes the rest of us their parents.