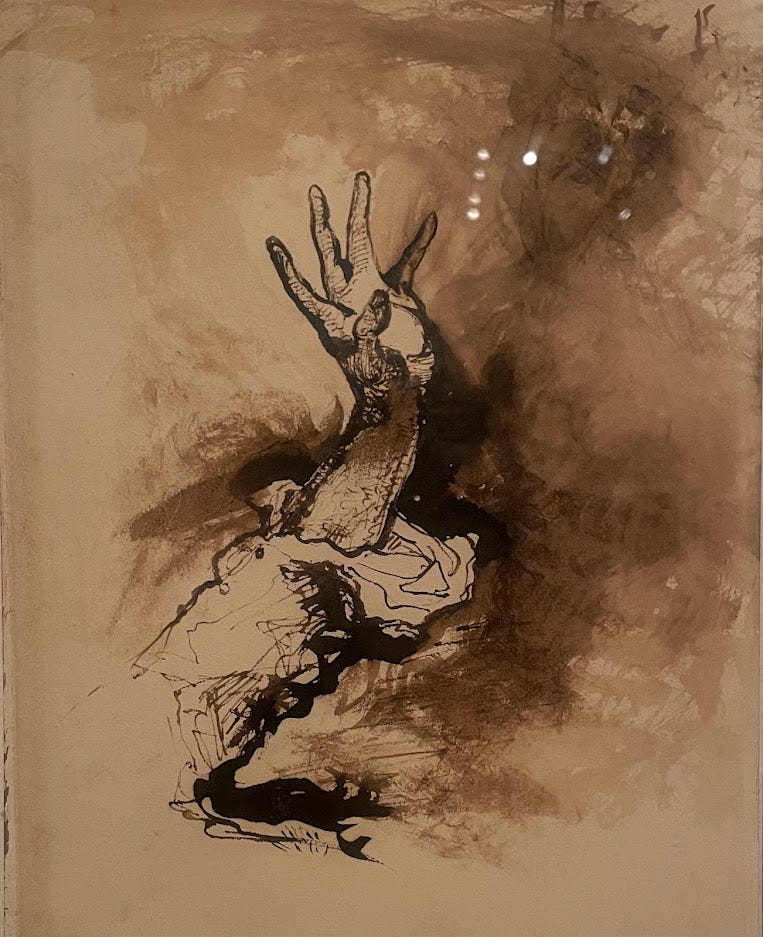

The Dream, 1866

The Dream is a mute hand groping at nothing, a drawing in wet ink and smoky wash by Victor Hugo. Hugo drew it in 1886 when he was no longer writing and stuck in political exile on Guernsey, where he would be marooned for another four years until the end of Napoleon’s Second Empire.

The sketch, more suffocating nightmare than ephemeral dream, is among 70 superb pieces in the Royal Academy’s Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo - a brief, taught show in the Sackler wing, and a revelation on a little-known episode in the history of 19th-century graphic art.

Hugo’s teenage daughter had been killed in a drowning accident in 1843, and her loss left him undone. Later, he stopped writing for a time after Napoleon denounced him as an enemy of the French state. But he always drew - seemingly for private reasons. These are works from the depths of despair, mostly from imagination, certainly from the subconscious. They are expressions of incurable grief.

Planet-Eye, 185

Théophile Gautier, the French art critic and Hugo’s contemporary, wrote that Hugo “excels in blending the chiaroscuro effects of Goya with the architectural terror of Piranesi”. That is technically true, but I don’t think Hugo’s illustrations are stagey. Mostly, his drawings foreshadow those of Mervyn Peake (whose archives were acquired by the British Library in 2020). They are not gothic in the sense of high drama - they are woozy, silent nightmares.

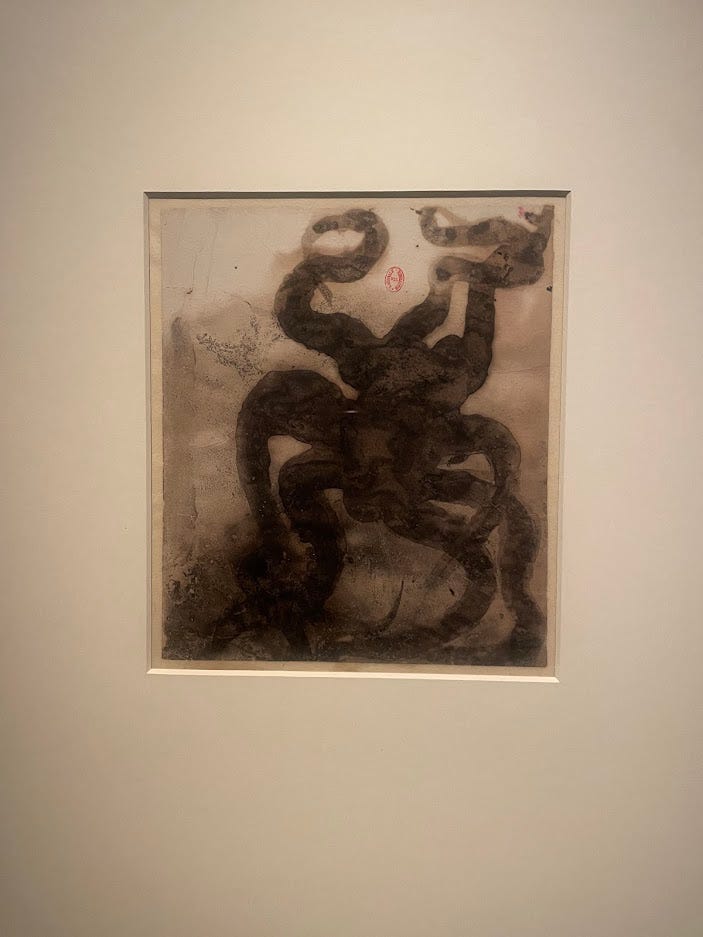

When I visited, a crowd had gathered around The Octopus - a motif that appears twice in the show: first in 1864-6 as “a glutinous mass possessed of a will… glue filled with hatred” (as Hugo described the creature in his 1866 novel Toilers of the Sea); second in 1886-9 as a monstrous black form. In both, its tentacles are contorted into the initials V.H.

The Octopus, 1886-9

About 3,000 of Hugo’s illustrations survive, of drowned or melting worlds, shattered edifices, evil weather, willful creatures, suffocating nightmares. At the Royal Academy, most are on loan from Maisons de Victor Hugo in Paris and Guernsey and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Because little is known about them, there is little context to distract us, other than their oblique titles.

Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo at the Royal Academy until June 29

Frozen People is a serious dance music festival with a jokey name. The joke is about the Burning Man festival because, unlike its American Western desert counterpart, the people who attend this gathering in north-west Finland are dancing on the frozen sea. And it is for people because it's in Finland, where everything is gender inclusive (“to be more equitable,” is how Heikki Myllylahti, the festival’s director, puts it to me.) Finns are nothing if not self-aware.

A Finnish DJ in a heated capsule

Frozen People, which is held in Oulu, about 140 miles from the Arctic Circle, is astonishingly beautiful to look at: tents are lit up like scattered diamonds in the black night, with DJs shrouded behind heated cabins. This being Finland, it's free and state funded. Though the sea ice is no longer reliable because of rapid climate change. In March, the ice is usually 70cm thick; when I visited a few weeks ago it was 30cm, and everyone said the winters were increasingly wet. “We have to measure the ice so people don’t drown,” says Myllylahti. Next year, 2,000 frozen people may have to decamp again to the city’s slushy shores.

Finns are tense because of the threat of Russian aggression (the country’s border with Russia, about 200 miles from here, is about 800 miles long). But young people are relaxed. Oulu has a massive underground bunker that could accommodate the city’s entire population - tens of thousands of people - in a nuclear attack. Those people I talked to were more interested in dancing than existential threats.

Next year, Oulu is European capital of culture, and the festival will get even more funding, so it will be bigger. Whether it will be on ice, no one can say.

Frozen People takes place in March 2026

There is always a Picasso exhibition somewhere because, like Shakespeare and the Beatles, there is always something new to say - a new fact to mull over, some unexplored aspect, a new scandal or relevance to old themes. And there is a lot of Picasso - he went on and on and he made about 50,000 art works.

One of the most ambitious Picasso shows in ages opened at M+ in Hong Kong’s last week. I couldn’t imagine a better backdrop than Herzog & de Meuron’s neo-brutalist mega gallery for Picasso for Asia - A Conversation, so I went to see the exhibition before Art Basel. The show is ‘for Asia’ because the point is to interpret the Spanish artist for an increasingly Picasso-curious Asian audience. Picasso is selling well here.

Massacre in Korea, 1951

What sets the M+ show apart is its breadth and rigour, as I wrote in my review for the Telegraph. The star is revealed at the end: Massacre in Korea, a 1951 painting in which an armoured, masked firing squad takes aim at a group of women and children, and - despite his output - the artist’s only work dealing with Asian subject matter. All Picasso’s attention is on the victims’ faces, and how each responds to brutality: anguished, serene, bewildered, detached. This is far from propaganda: here, at least, Picasso treats women as complex, sympathetic and deeply human.

He did not always treat them like that, as the show acknowledges in a room dealing with his misogyny. It makes the point and moves us on, which may not be ideal but neither was the hectoring, clunkily titled 2023 show at the Brooklyn Museum, It’s Pablo-matic. The Hong Kong curators, Doryun Chong and Francois Dareau, trust us to absorb Picasso’s contradictions.

Picasso for Asia is at M+ Hong Kong until July 13

More things I enjoyed:

Also at M+ in the main collection - a collection of design drawings for Hong Kong neon signs from the 1930s to the 1970s, from the archives of the Neco Neon Company.

Lives less Ordinary: Working Class Britain Re-Seen at Two Temple Place, until April 20. It takes courage to tackle social class, so this show, curated by Samantha Manton, feels fresh and bracing. My review and interview with Samantha for the Telegraph is here.

Soane and Modernism: Make It New at the Sir John Soane Museum, until May 18. Includes a fragile drawing for the K6 telephone box by Giles Gilbert Scott. My piece on the exhibition for the Telegraph is here.

Deconstructed - A new-ish monthly podcast from Open City hosted by the always-upbeat architectural historian Matthew Lloyd Roberts, in which he explains the architecture of buildings to help us understand what makes them compelling. The first episode is an excellent guide to Hawksmoor’s St Anne’s church, Limehouse.

Les Rendez-vous d’Anna - I saw this 1978 film by the cult-ish Belgian director Chantal Akerman at the BFI as part of its recent Akerman season (the film is now on BFI Player). It’s an Akerman quasi self-portrait, the story of a film director trundling around cold-war Europe trying to outrun her terrible boyfriends as it dawns on her that she prefers women. It’s more conventional than Akerman’s best-known film, Jeanne Dielman. There are no endless Warholian silences. But I prefer it - it’s a small masterpiece.

On my list:

The Venice Architecture Biennale

Morris Mania at the William Morris Gallery

Crisis Point: artistic perspectives on mental health and the criminal justice system at Bethlem Museum of the Mind

What I’m working on:

A story about the birth of skyscrapers

A longform piece about secret culinary lives

A story about UK film studios

A story about restoring modern art

Various book reviews