Battersea Power Station was hated in the early 1930s. Londoners were furious at its size and its obtrusiveness. It was too grubby, too blank, and its business of burning coal too dangerous.

They were right about the latter. So Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s brick mass on the banks of the Thames, like some art-deco cliff-face - was decommissioned 50 years later. By that time, it was cherished and listed - then left to rot. Empty and with its roof removed, those sleek interiors were open to the elements and abandoned to colonies of foxes for more than three decades.

Now, Battersea is about to open again as a mix of luxury flats, shops, Apple offices, a cinema, events space and so on. It is a huge undertaking. Think of Tate Modern then double it for a sense of the scale of Battersea’s two turbine halls.

But Battersea Power Station redux is far from pristine. When I went to look around on a preview tour, I was struck by how gnarly its retrofit by WilkinsonEyre is.

Scars are on display - gashes on the bricks, occasional gaps where tiles have fallen from walls. We are left to reflect on how careless we have been with our industrial heritage, though there is nothing pious - or even overt - about how Battersea’s damage is presented.

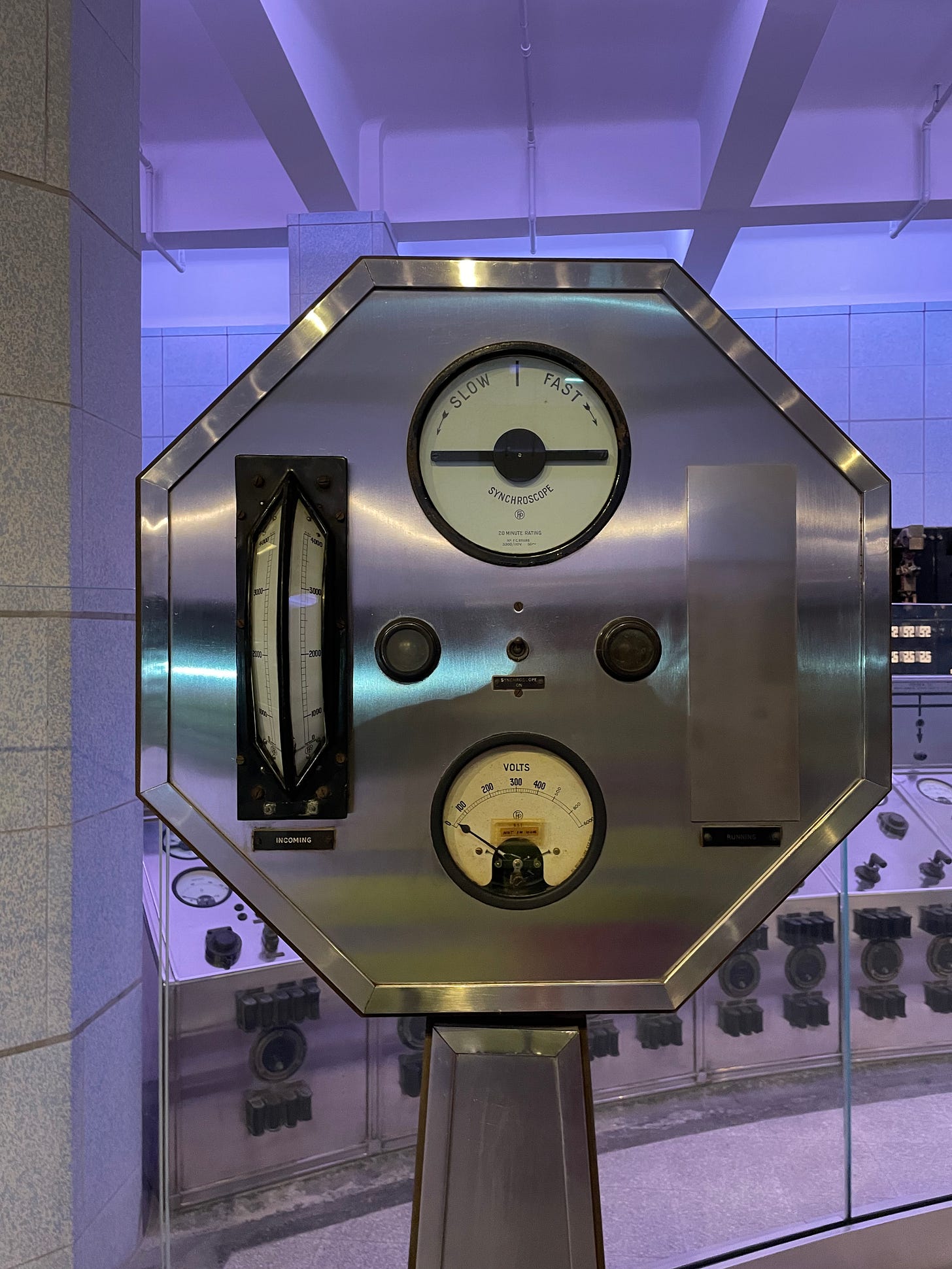

Take the turbine hall control rooms - there are two, one for each hall - where industrial futurism meets goofy anthropomorphism. In Control Room B - built in the 1940s and 50s and soon to become a bar - the synchroscopes stand like real beings, and just as tall.

But where their dials are broken and bits have fallen off, they have been replaced not with replicas but with blank space - like this metal plate on the right-hand side covering the gap where a gauge used to be.

It’s all so seductive. Here’s Control Room A. It is more Hollywood than south London. There is a glass and gilt ceiling, carved stone walls, an oak parquet floor and balconies. Who puts balconies in a power station?

According to the architectural historians, all this was all to give the London Power Company’s investors, who had paid for the place (or might want to), a sense of the drama and thrill of energising London in the 1930s - industry as theatre. In its new life, it will probably be a place for parties and events.

From the autumn, one of the Thames-side chimneys will house a lift with a roof-top viewing gallery (which pops up then pops down again, so as not to ruin the symmetry) and a run through the cultural and iconography “story”, including the Pink Floyd and Hawkwind bits. The lift will be charged for, but other exhibitions will be free.

Old equipment - dusty, dented hulks of machinery - have been salvaged and installed inside and out in lieu of commissioned sculptures, which feels exactly right.

Battersea’s relationship to the Thames is the most fascinating part. River water was used for cooling and coal deliveries. The land here is marshy. In the power station’s derelict years, people said you could stand inside and feel its heft shift with the tide. Former workers are contributing their oral histories to exhibits.

There are, I’m told, tales of secret escapes through the cable tunnels under the Thames to Chelsea pubs on Friday lunchtimes.

There is a lot to quibble about in the wider Nine Elms development. But regardless of how Londoners feel about the overbearing residential blocks and the Sky Pool, they will probably love the 21st-century iteration of Battersea Power Station.

I will miss the mystery of its desolate state. But it is no longer rotting.

There are many more gnarly brownfield redevelopments, recent and opening soon. They are much smaller than Battersea but miraculous in their own ways. I have written about them for Telegraph Arts, in a feature to be published shortly.

Battersea Power Station opens in September.

I know it’s out of fashion, but I still love a white cube. One of the best is Turner Contemporary, the gallery that has probably come closest in the UK to replicating the elusive Bilbao effect. I have never seen a duff exhibition in Margate, and the place is always rammed.

Ingrid Pollard’s Carbon Slowly Turning exhibition of photography, film and installations is almost a career retrospective, but not quite. She prefers to call it a survey.

It includes Self Evident, her 1994 series of photographs of people posed in English landscapes, holding incongruous and loaded objects. Like this guy standing in an arable field holding a box of fried chicken.

I interviewed Pollard in the galleries, just before the exhibition opened, for a forthcoming FT Life & Arts piece. One of the aspects of the show that I didn’t have room to write about was this sinewy, kinetic sculpture: Bow Down and Very Low - 123, which Pollard made last year.

I find bowing and curtsying mindless and faintly repulsive, and Pollard is deeply suspicious of these gestures, too.

Each of her three characters moves in a random dialogue: the one on the left flails the baseball bat into thin air; the one on the middle bows and scrapes and the third lunges like a blind thug. They are both threatening and deferential.

And they are deafening - they squeak, scrape and clank. The noise from that rusty saw does something disturbing to the nerves in my teeth and the back of my neck. “Yeah, it’s not a gentle sound,” Pollard says.

It seems to be about the power dynamics that go with bowing and curtsying (there is a photograph of a curtsying child displayed alongside), but beyond that, Pollard’s work offers few clues. There is no puzzle to solve, no neat explanations, and Pollard is not interested in flattering us on our understanding of her work. She leaves us to work out what’s going on, what the tension might be and how our own experiences affect what we see.

The figures in the sculpture are prompts, she says: “Who is doing the bowing? Who is receiving it? Where is the conflict and how do you resolve it?”

Pollard found the photograph of the child in the BFI collection, part of a piece of postwar film. “She was in a Northamptonshire school and the other children had voted her May queen,” she told me. “So why is she curtsying to them? And in the film, the gesture is repeated when she’s crowned.”

If the girl is the queen, who is the authority? And who is recognising it? Why must she demonstrate submission in order to be admitted?

Like I said, curtsying is troubling.

Carbon Slowly Turning at Turner Contemporary until September 25

Lew Allen’s photographs from the mid 1950s capture the mayhem at the birth of rock and roll.

He shot them in Cleveland and New York, often on bus tours where artists travelled across the US together and performed on the same bill; helped each other; carried their own stage outfits and equipment and were backed in each town by the local orchestra.

Elvis takes centre stage in Allen’s collection. He looks permanently stunned, and so do his fans. They can’t believe what they are seeing and hearing, and it is as if no one is in control of themselves. The Everly Brothers, Bobby Darin, Frankie Avalon and Buddy Holly are here too.

But the highlight was Eddie Cochran’s Lost Locker Collection: a stash of ephemera stored by his family in a lock-up after his death at 21 in 1960 in a car crash in rural England. The collection was discovered in an auction last year.

Including this last letter from a former girlfriend:

Elvis & The Birth of Rock at Proud Galleries closed on June 25

On my list:

Italy, to see the Donatello exhibition at Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi in Florence before it closes

Switzerland, to see Heidi Bucher Metamorphosis II at Muzeum Susch

A Thing for the Mind at Timothy Taylor

The Immortal at Elizabeth Xi Bauer

A Way From Home: Longing and Belonging at Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Maeve Gilmore at Studio Voltaire

What I’m working on:

An interview with a Nordic fashion wunderkind

A feature on a neglected postmodern fashion designer

A piece on regrettable holiday fashion buys

A piece on bad walking tours

A story about reclaimed arts venues

A story about new auctions

Several artist interviews

A piece on modern performance art

In awe of your eclecticism. How do you find time? How do you keep so much on the boil?