Copenhagen, Royal Academy Schools, Goldsmiths Contemporary, Barney Bubbles

Cultural notes - fortnightly

Copenhagen I

Three Days of Design is an equitable extravaganza.

No booking required; events are free - as are the parties, wine, beer, coffee, even the cinnamon buns. It’s for anyone who wants to poke around, meet designers and ask questions - not just trade, cognisanti and industry gatekeepers. Is it worth your time? Almost certainly.

There is no restricted access, velvet rope or VIP anything. Just turn up on one of the three days in June when the Danish design industry opens up with trays of scran. A bunch of Brits kept marvelling at the Scandi informality: (“Imagine all this in London! A bunfight!”).

Crowds of people drift through showrooms and workshops for hours, well into the white nights, draining flutes and admiring the endless lampshades. I turned up for one and a half days in mid-June with only the vaguest understanding of this festival that styles itself somewhat self-consciously as 3daysofdesign and is now in its ninth year.

That was enough time for three lectures (example: a panel of Danish interior designers trying to work out why office workers don’t want to work in offices); eight dressed townhouses and four showrooms - even a lost hour in the wildly popular Fritz Hansen pavilion by architects Henning Larsen; a gallop round the recently refurbished Danish design museum and a quick trip out to the beach suburb of Charlottenlund to ogle Arne Jacobsen’s 1938 petrol station.

Three Days of Design founder and director Signe Terenziani was at an event to celebrate dining tables, hosted by art concept retailer &Tradition. Five furniture makers from around the world had reimagined a table each. One had produced a giant plastic tulip; another a lethal looking sheet of aluminium.

We were seated at a glass ziggurat balanced on bronze boxes, with different shapes allocated to introverts and extroverts - the work of the South African designers Stellenbosch Art Foundry.

Terenziani told me she started Three Days of Design with local brands from her own dining table and fitted it around her day job. It’s a non-profit, what she calls a framing event for an industry the Danes take as seriously as fine art.

A Danish stylist in one of the extroverts’ seats was between parties and openings. I asked her what kept her awake at night. “Invasion,” she said. “Or the thought of it.”

The same night, Russian warships were chased out of Danish Baltic waters by the navy.

Copenhagen II

At SMK, the Danish national art gallery, four six-fingered hands are clad in jingle-bell gloves, clutching something like a jingle-bell globe, with red plastic handles attached to a raffia cuff.

The five-foot caboodle rests on casters, waiting to be wheeled around, which the gallery assistants do now and then with a ‘Hi Hi!’. We stand back to watch as they scuttle across the buffed blond-wood floor, and come to rest where they will.

In February I interviewed Haegue Yang over Zoom for Sotheby’s Magazine, just before her SMK show opened. She was in her studio in Berlin, tired, concerned about war in Ukraine, a little despairing. But she was also keen to explain the twin sculptural figures she had created for her multi-sensory show, Double Soul.

There are dozens of her works here, but this pair - Six Fingered Wayfairer after Arke, which is the giant scuttling jingle-belled hands, and their partner, Tripodal Shapeshifter After Ferlov Mancoba, which is perhaps a blind horse - was made especially for Copenhagen.

Yang’s faceless figures are deliberately unsettling. They suggest folklore, maybe voodoo - something indifferent with unknowable intent. For her Strange Attractors exhibition in St Ives in 2021, they were corndollies the size of teenagers, possibly dupes of the Morris dancers on the quayside outside. In Copenhagen, they are something else entirely.

She is from South Korea - a childhood disrupted by civil war - but now lives and works in Germany. This is an artist concerned with the split self; the double life of the displaced.

Yang told me how, in preparation for the SMK show, she rootled around in the Copenhagen state archives and found big sealskin mittens with curious double thumbs, like bunny ears. They belonged to colonised Inuit hunters in Greenland, where constantly pulling on reins on long hunting trips is a gruelling business. Thumbs on mittens wear out quickly; double-thumbed mittens can be swivelled around to solve the problem.

Yang named the scuttling hands after Greenlandic-Danish artist Pia Arke. She also spent time in the SMK main collection, where she had been struck by the work of sculptor Sonja Ferlov Mancoba, a Danish surrealist-modernist. Ferlov Mancoba thought of her figures as living creatures who had to be able to stand on their own feet before being sent out into the world.

Yang told me she chose to base her pieces on the work of Arke and Ferlov Mancoba because “both have a diasporadic relationship with Denmark, drifting away but still tied with Danish history and artistry”.

I went to find Ferlov Mancoba’s sculptures in the main collection. They are by far the best work in the Danish surrealism galleries.

The Greenlandic Inuit mittens and Mancoba’s scuttling figures are right there in Double Soul. The connections Yang makes are extraordinary.

Copenhagen III

The Danish see design as an intellectual challenge, something central to a better life, a serious quest to improve and elevate. There is even a Bake-Off style television contest, with teams competing to design a classic piece of homeware. Why do they take this endless quest for simplicity and rationality so seriously?

There are theories: an early 18th and 19th century middle class; a shortage of materials after the second world war; welfare principles; state investment. All of that is true. What is also striking is just how much reflection, of thinking about design, the Danes do.

Copenhagen’s Design Museum Denmark reopens this month after a two-year hiatus. The galleries have ben revamped and redesigned since I was last here more than two years ago. I went to take a look.

There are a lot of displays about the process of design.

Earlier in the month I had interviewed Denise Hagströmer, design curator at the new National Museum of Norway in Oslo, for FT Weekend magazine. She talked about how, in starting design galleries from scratch, she had struggled with the question of what a design museum is for. Is it to showcase industry? As a repository of good taste? Should it try to be something like the V&A? Or something entirely different?

Her counterparts in Copenhagen had been asking the same questions. There are new galleries to showcase the usual legacy stuff - vitrines and cabinets full of silverware and snuff boxes and ornamental shields for Japanese swords. There is an amusing gallery of retro futurism and an earnest exhibition about design and sustainability.

The modernist and postmodernist chairs, lamps and so on are stuffed into a few galleries at the end. It’s better, perhaps a little bewildering.

I miss the chair morgues. The curators say they will be back later this year.

Design Museum Denmark: open now

London I

Graduate shows give us a flash of the future. The fun is in trying to spot the artist with the most to say, or the one who is most audacious, or the one responding in a wildly different way to the same stimuli in the same era.

At the Royal Academy Schools Show, I thought that was Kobby Adi. In a blur of loud multimedia installations and giant, cartoonish canvasses, Adi’s work is so subtle, so ambient, it is barely there.

In a painting studio in the depths of the schools, Adi has removed all the plaster casts. I have no idea what they looked like in situ, but I have a good idea because their scars are evident all over the walls, their streaks, indentations and impressions. They are ghosts, and he offers no explanations.

London II

South London’s best gallery is the Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, a raw and soaring space around the back of the Goldsmiths campus, adapted by Assemble Architects from the old pump house attached to Victorian swimming baths.

For its current exhibition, Tennessee sculptor Virginia Overton has taken a storage container full of Anthony Caro’s metal off-cuts, which had corroded after the sculptor’s death in 2013, and turned them into an extraordinary collection of abstract sculptures.

I was there to talk to Sarah McCrory, the gallery’s director, about another project, but I got distracted by the enormous shapes, and she generously showed me around.

We talked about how there’s something of the farm-equipment geometry about Overton’s pieces (Overton works in New York but she grew up on a vast industrial farm and is clearly fearless around large bits of metal). The pieces she has produced seem to be about worth, what we assume to be worthy, and worthy inheritors.

London III

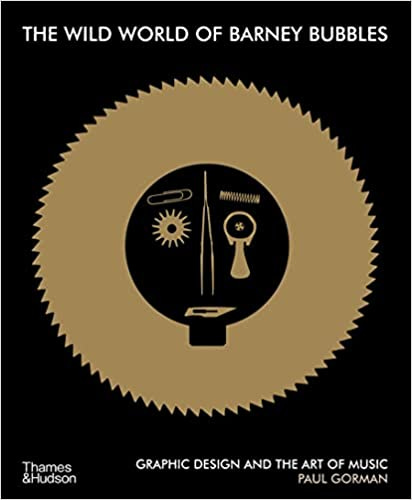

Barney Bubbles’ designs for record sleeves in the 1970s and 1980s were the most sophisticated visual interpretations of popular music. Peter Saville called him “replete with anarchic intelligence”; Peter Blake said: “Barney Bubbles is so good I could never have competed with him”.

Bubbles was - and still is - relatively unknown. That is partly because he was an elective enigma. He gave only one interview to the Face in 1981. He killed himself in 1983, at 41 after years of mental illness. He hid behind pseudonyms.

As Paul Gorman suggests in his about-to-be republished Bubbles monograph, his subject was also displaced by a new era of CDs and MTV. Bubbles’ death came six weeks before the invention of the Apple Mac.

If Gorman hadn’t written his monograph, Bubbles would be at risk of slipping out of history. The updated version with a touching Bubbles self portrait on the cover and a new essay by Saville is published at the end of the month.

I did an in-conversation with Gorman last week as part of Mark Hart’s excellent Rock and Roll Bookclub series. In the audience were people who had known and worked with Bubbles. Their recollections made the evening extraordinary.

Gorman talked about how he tracked down Bubbles’s art school friend, Lorry Sartorio, who gave him ephemera and artwork that she had been waiting for someone to show interest in.

Read me this month in:

The Financial Times

The secrets of Stonehenge could be lost forever

‘He was his own maker of style’: Elvis’s costume designer on reimagining a legend

The Norwegian museum that’s redefining design

The Telegraph

The truth behind Munch’s The Scream

What I’m working on:

An interview with a Nordic fashion wunderkind

A feature on a neglected postmodern fashion designer

A piece on regrettable holiday fashion buys

A piece on bad walking tours

A story about reclaimed arts venues

A story about new auctions